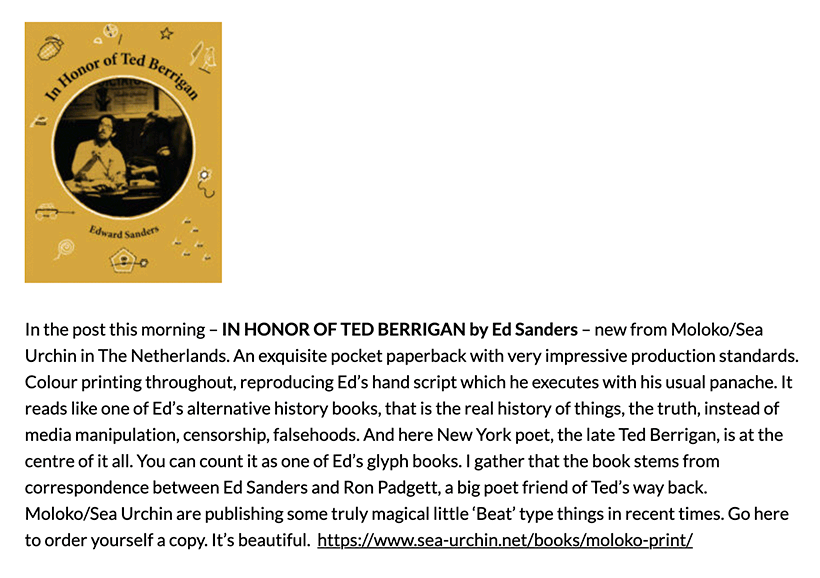

Review of In Honor of Ted Berrigan by Ed Sanders in Beat Scene #104, early Summer 2022.

Review of In Honor of Ted Berrigan by Ed Sanders in Beat Scene #104, early Summer 2022.

I’ve never been much of a collector. I prefer to travel light. Besides, most of the books that turned out important to me as a student or artist were library books, borrowed for lack of money to buy copies of my own. Other important books belonged to friends, or were lent to friends and never returned and yet others were donated to a charity bookshop when I moved house a couple of years ago. In this short list I have limited myself to those books that have been in my possession for a long time and have somehow survived the ravages of time. –Ben Schot

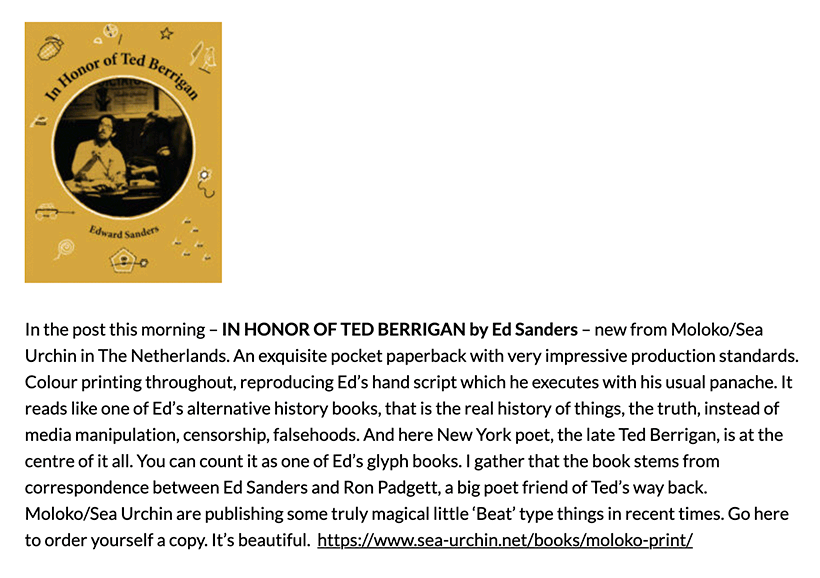

1 Ryam school diary 1966-67

This publication didn’t so much inspire me as provoke me to vandalize it. Ryam school diaries tried to appeal to secondary school kids with pictures of bands and movie stars in the 1960s, but we thought they were downright corny. And ugly. We hated them. So what kids our age did all over The Netherlands, was cut pictures of their favorite bands from music magazines and paste those over the pictures in our diaries. Page after page. As many as possible. A friend of mine, Frank Verhage, had started the craze in our first form and I followed suit. Frank was a cool and lovable guy, a real music buff: well-informed about the latest releases and subscribed to more than one music magazine. As a result, his personalized diary had grown so fat by the middle of the school year that it exploded. Stuffed with pictures of The Who, The Beatles, The Stones, Pink Floyd, Q65, The Monkees, The Small Faces and many others, mine burst at the seams not long after. For some reason I kept this school diary all the time and when I took up publishing many years later, I liked to think of this keepsake from 1966-67 as the first book I put together. I only parted with it when it was included in the city archives of the town where I grew up a couple of years ago. As a document of the 1960s. Ha, how about that, Frank? That must have cracked you up in rock & roll Valhalla like your own school diary did more than fifty years ago.

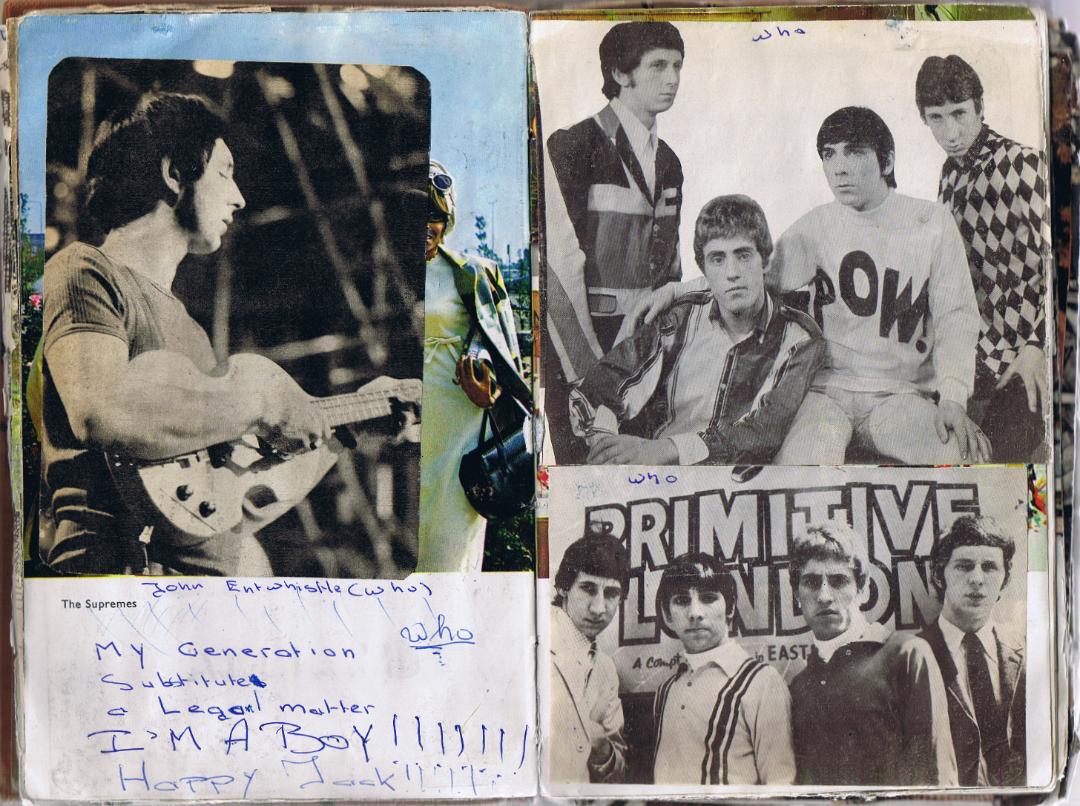

2 H.P. Lovecraft – Het Gefluister in de Duisternis

The ownership signature and date that I left on the first page of this book say 26 July 1969. I was 15 at the time and having a summer holiday. I don’t remember buying this particular book but it must have been in one of the touristy shops under the dunes of the isle of Schouwen-Duiveland, where my parents spent each summer in a trailer. The Lovecraft compilation ‘Het Gefluister in de Duisternis’ had been published the previous year as one of the ‘Zwarte Beertjes’, a series of cheap Dutch paperbacks published by Bruna, Utrecht. The books were very popular and ranged from Ian Fleming novels and Georges Simenon detectives to science fiction by Moorcock and Asimov, and compilations of Edgar Allan Poe tales. All in Dutch. I must have read dozens of them in the 1960s and early 1970s. I don’t remember much of the Lovecraft tales of ‘Het Gefluister in de Duisternis’ themselves but I do recall the fear they sparked. My nerves were on edge the summer of 1969 anyhow. It was a period of violent conflicts at home. Of love and friendships lost. Of an inevitable breakdown. In the daytime I wandered across the dune region and hung out at an amusement hall, at night I hardly slept at all. Yes, Lovecraft’s book sparked impalpable fears of the supernatural but the horrors were very real that summer. Cthulhu = pussy.

3. Albert Camus – Dagboek

The first time I read an Albert Camus book was in café ‘De Vlinder’ in the country town of Zierikzee in the early 1970s. ‘De Vlinder’ (The Butterfly) was a countercultural café run by Bob and Mimi de Rooij, a married couple from Rotterdam, and was home to socialists, pacifists, artists, musicians and local freaks like me for a couple of years. Camus’s ‘Myth of Sisyphus’ was on the reading table of that café, next to ‘underground’ magazines such as ‘Aloha’ and ‘Suck’, the first European sex paper. A powerful brew for a kid my age. ‘The Myth of Sisyphus’ inspired me to buy other books by Camus from one of the bookshops in town: Dutch translations of ‘L’Exil et le Royaume’, ‘L’Homme revolté’, ‘L’Étranger’, ‘La Chute’ and ‘Carnets’, a selection of journal notes from the period 1935-1951. The ownership signature and date in the latter mention 1974 as the year of purchase. That was the year ‘De Vlinder’ changed hands, never to return as a countercultural café, and I was at home, studying English language and literature while awaiting the outcome of the procedure that pacifist conscientious objectors to military service had to go through in those days. I internalized Camus’s concepts of exile and rejecting nihilism in that period and cherished the fragmentary notes in his ‘Dagboek’ like crumbs of bread leading me out of the woods of alienation: ’The red light district is called “Truth Street” here. The rate is three francs’. I kept my copy of Camus’s ‘Dagboek’ ever since, took it on journeys sometimes and kept it at hand in my first studio in the early 1980s. It was there that it got stained by the tar that I used in drawings and collages at the time. Tar, the smell of which reminded me of the quay in Zierikzee where I used to live when I bought the book and the black water of the harbour was teeming with nihilist sirens at night.

4. Jacques Lacan – The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis

During the period in the 1970s that I was doing English language and literature at home and awaiting the outcome of the procedure for conscientious objectors, I studied works by Freud and Nietzsche alongside those by Albert Camus. The Nietzsche-Freud-Camus triangle proved fruitful for me as an artist and has lost none of its power since. Years later, after I had finished art school, I bought a paperback edition of Jacques Lacan’s ‘Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis’, but apart from the section where the eye and the gaze are discussed, the contents of the book remained obscure to me. I believe in psychoanalysis as a means of laying bare the inner workings of our psyche and culture, but most of Lacan’s work is beyond my reach. Still, I kept the book. And yes, every now and then I look up a thing or two in it. But each time I reach for the book I can’t help thinking that Lacan’s theories are outdone and outsmarted by the reproduction of Hans Holbein The Younger’s ‘Ambassadors’ on the cover. ‘The Ambassadors’, with its skull painted in anamorphic perspective in the foreground as a subtle and fleeting ‘memento mori’. A skull visible only to passers-by and invisible to those focusing on the noblemen and their riches in the painting. Death, as Lacan tells us in so many words, truly is King.

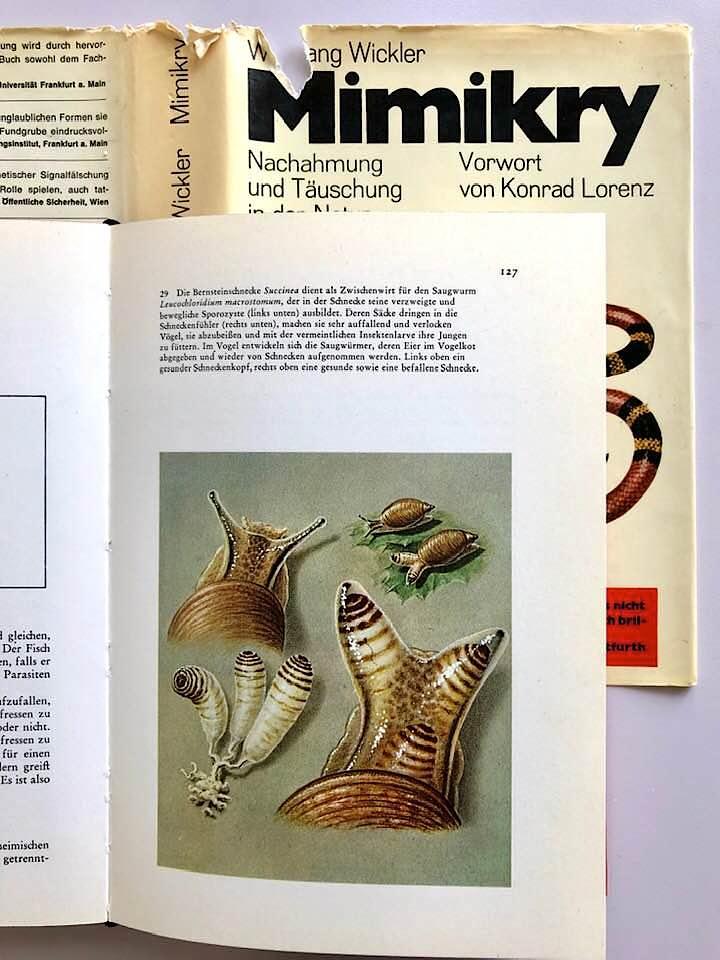

5. Wolfgang Wickler – Mimikry

In his ‘Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis’ Lacan compares art to mimicry in nature. If I remember correctly, Lacan states that the biological function of mimicry in nature, in which one species imitates another, can be summed up as either ‘camouflage’, ‘intimidation’, ‘travesty’, or combinations of those. I thought that was a fascinating concept, worth looking into and possibly worth exploring in my own work. After having put Lacan aside in the mid-1990s, I bought an antiquarian copy of zoologist Wolfgang Wickler’s ‘Mimikry’ (first published in 1968) and believe I devoured the book in a single night. Insects with false heads on their hind parts, a praying mantis that looks like a flower, male bees that are more attracted to the fake female bees that some orchids present to view than real females, cuckoo eggs that surreptitiously fool their hosts… mind-blowing stuff. One of the cases of mimicry described by Wickler drew my attention in particular and when I found out that a VHS tape of this phenomenon could be ordered from a scientific institute in Göttingen, Germany, I bought a copy and subsequently screened it during a talk about my work in one of Rotterdam’s art institutes. The video showed how a parasite, a worm, that lives in the intestines of birds follows an unusual cycle of asexual reproduction. Once the eggs of the worm have been defecated by the bird, some of them are consumed on the ground by snails that feed on bird shit. Inside those snails’ bodies the eggs develop into sporocysts, sacks of larvae, which work their way up to the snails’ eye-stalks. And once there, the sacks start pulsating and look so much like live worms that the eye-stalks are often snapped off and eaten by predatory birds. Inside the digestive systems of those birds the cycle starts all over again. It’s a cruel and perverse universe. And art, sweet art, can only lick Mother Nature’s boots.

First published on Cary Loren’s website The Book Beat.

Interview by John Wisniewski

Interview by John Wisniewski

John Wisniewski: When did your career in art begin, Ben?

Ben Schot: I wanted to go to art school when I was in the final years of secondary school. My art teacher was Ad Braat, a local sculptor who liked my drawings and advised me to enroll in art school. Once I had made up my mind to follow his advice, he prepared me for the entrance exam of art schools with a couple of private lessons in the summer of 1971. I still have one of the many drawings that I did in that summer. I was 17 at the time. Braat’s enthusiasm and his expressionist, alcohol-fueled views were inspiring and liberating. They loosened me up and made me feel a bit more confident about my work, but his teachings weren’t much of a preparation for art school, which for the greater part consisted of formal and technical trainings in those days. I failed the entrance exam that year, and the next, and then was drafted for military service in 1973. Other sources of inspiration in 1970-71 were a school trip to a large Dali exhibition at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam and the scene around a countercultural café that Bob and Mimi de Rooij, a married couple from Rotterdam, had started in the small country town where I lived. Bob and Mimi were also at the heart of a club that screened films by Godard, Fellini, Bellocchio and many others in the school auditorium. For a couple of years those films and the café were wild orchids in the dunes of cultural life on the island where I grew up.

Once I had refused to do military service and had to go through the long procedure for conscientious objectors to be officially recognised, I started studying English at home awaiting the outcome of the procedure. I was recognised as a pacifist conscientious objector in 1976 or 1977 and then had to do alternative military service – the longest possible time the authorities could hold you. All in all the procedure and service took some 5 years. Not long after having been relieved from alternative service I obtained a teaching degree in English and together with Joleen, my then girlfriend, left the island in the south-west of The Netherlands, where we had lived until then. Joleen entered the art school of Utrecht and I took a job as an English teacher at a secondary school in Gouda in 1979. After having taught English for a year and a half there, I became restless. The desire to be trained as an artist flared up again. I quit my job and took classes to prepare once more for the entrance exam of art schools. This time I was admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts in the Hague. That was in 1981. I was 27 at the time. I did art school in The Hague for two and a half years and then switched to the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam, where I lived. I graduated there in 1986.

John Wisniewski: when were your first exhibitions?

Ben Schot: My first group shows were in 1986 and 1987 in Rotterdam, not long after I had graduated from art school. Then, in 1988, I showed a couple of large drawings in combination with sculptures by Eric van Solm, another starting artist, at CBK, the Arts Centre of Rotterdam, and in 1990 I did my first solo exhibition at Galerie van Kranendonk, The Hague.

John Wisniewski: Could you tell us the story of how sea urchin books began?

Ben Schot: Already at art school I looked for ways to combine texts, drawings, photos and found images. Books are perfect for combinations like that. In those days I sometimes put together primitive hand made ‘books’, loose sheets of paper crudely taped or saddle-stitched together. I made those for private use, unique copies as a sort of notebook or sketchbook. Then, after I had left art school, came a couple of xeroxed and saddle-stitched editions in runs of 5 or 10 copies, which I handed out to friends and colleagues. And then, with the help of subsidies and grants, followed offset printed artists’ books in runs of some 500 copies, which I published under an imaginary imprint. When I came across an Edgar Allan Poe tale that was set in Rotterdam and had some money left from a grant, I decided to publish it under the imprint ‘Sea Urchin’, which was a reference to my youth in Zeeland, where my father made a living as a fisherman, and to Jean Painlevé’s surrealist film ‘Oursins’. The Edgar Allan Poe tale was published in 2000-2001. I had no idea what it meant to run a publishing house or what to expect, but to my surprise the book was well-received and sold reasonably well. The next year I published two books: Dutch translations of a scatological tale by Serge Gainsbourg, an old hero of mine, and of ‘Les Champs magnétiques’ by André Breton and Philippe Soupault, experiments in automatic writing that marked the beginning of Surrealism. For those translations I hired Jan Pieter van der Sterre, a respected Dutch translator, who taught me a couple of things about producing books, distributing them and getting them reviewed. The two books were well-received and especially the Breton/Soupault edition was widely reviewed in national newspapers. I used individual grants that I received as a visual artist from what is now called the Mondriaan Fund to produce more books in the next five years, such as Henri Michaux and Pier Paolo Pasolini translations. The director of the Fund at the time was Lex ter Braak, who was very sympathetic towards Sea Urchin, and didn’t seem to mind subsidies intended for visual art being used for literature. So, it’s fair to say that Sea Urchin began as a side product, as a logical extension of my practice as a visual artist.

John Wisniewski: What may inspire you to create, Ben?

Ben Schot: That’s a difficult question. I don’t really know. It also depends on what I’m working on: making books is a different process from drawing or writing. True, making books the way I do now, hand made editions of 15 copies, each with a hand drawn cover, comes close to drawing. I even like to think of them as drawings in the guise of books. And both products require concentrated manual work, thinking with your hands and eyes. But before I reach that point in making books there has been the process of selecting and designing texts or poems. In that selection process I have always consciously followed historical lines in literature that interest and inspire me. For instance the influence of Edgar Allan Poe on the European avant-garde. Or Nietzsche’s influence. Or both Nietzsche’s and Poe’s: now there’s a powerful brew that will take you places.

And then drawing… I’ve always liked drawing, even as a kid. I think for me as a kid it was a way of getting out of here, of opening another world. I had a lot to get away from where I grew up. It was also a way of expressing myself at the time. I remember on one occasion drawing a sort of mourning card when I was a kid after our cat had been run over by a garbage truck. As a way of expressing grief. But strong emotions like that don’t normally inspire me to start drawing nowadays. Maybe a kind of inner tension does. A subconscious inner conflict that builds up and needs the process of drawing to be sublimated, much like a dream. I don’t know. Usually the destruction of an older drawing or using a rejected drawing for the start of a new one is part of that process. I guess my drawings are fuelled by both destructive and creative impulses. Bastard babies that stare at you. Daddy?

I don’t think of myself as a writer but I write on a regular basis for Sea Urchin and I used to write articles for magazines in the past. Those texts require a lot of research, thinking and phrasing, work behind the computer. I don’t always feel like that. The inspiration for those texts is down-to-earth: you tackle a subject and try to communicate it in the best possible way. I hate translating prose but translating poetry can be a truly inspiring, challenging and rewarding process. Some poems scream to be translated, other resist, you have to find out and look for diamonds in liquified fat.

John Wisniewski: could you tell us about upcoming editions At sea urchin?

Ben Schot: Dreams! Dreams!

John Wisniewski: have you met many great poets, while operating sea urchin editions?

Ben Schot: No, not many. I was told they live on Mount Olympus, but I’m afraid of heights and allergic to laurel. But seriously, of all the well-known and lesser known artists, musicians and poets I have met and worked with since I started Sea Urchin, a couple stand out. Mike Kelley was a great artist: a keen, original and subversive mind. It was a real pleasure having smoked a pipe or two with Hugh Hopper; what a gentle and beautiful soul he was. Having met Mick Farren backstage at the same venue in London where he tragically collapsed a year later, was unforgettable. And having seen William Levy on a regular basis in the final years of his life was a true privilege. They were all great, each in his own way. But they’re gone now. Their spirits embedded and preserved in their works. I will only mention the dead here. The living, dear friends and colleagues, have voices of their own.

Source: AMFM Magazine