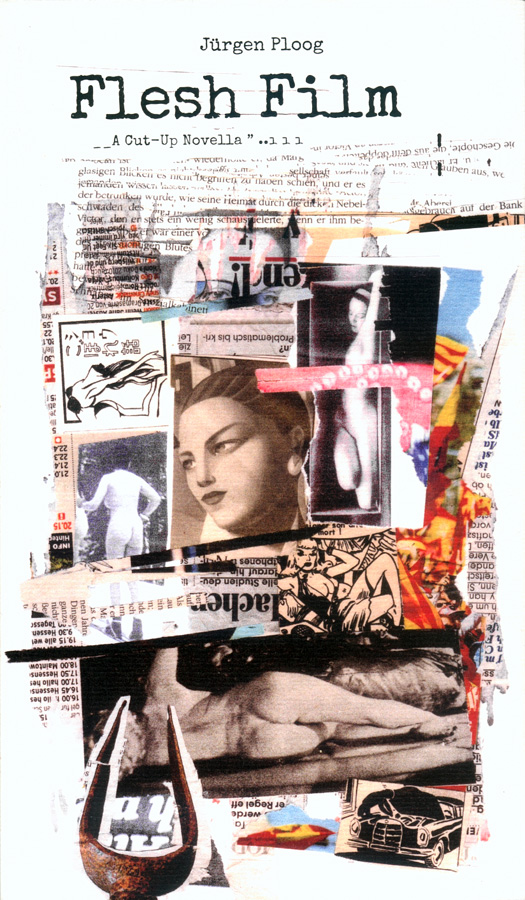

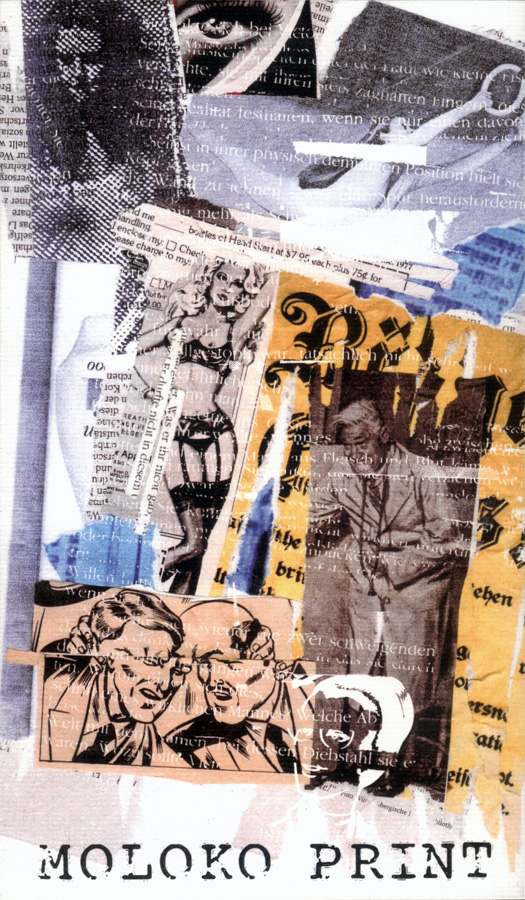

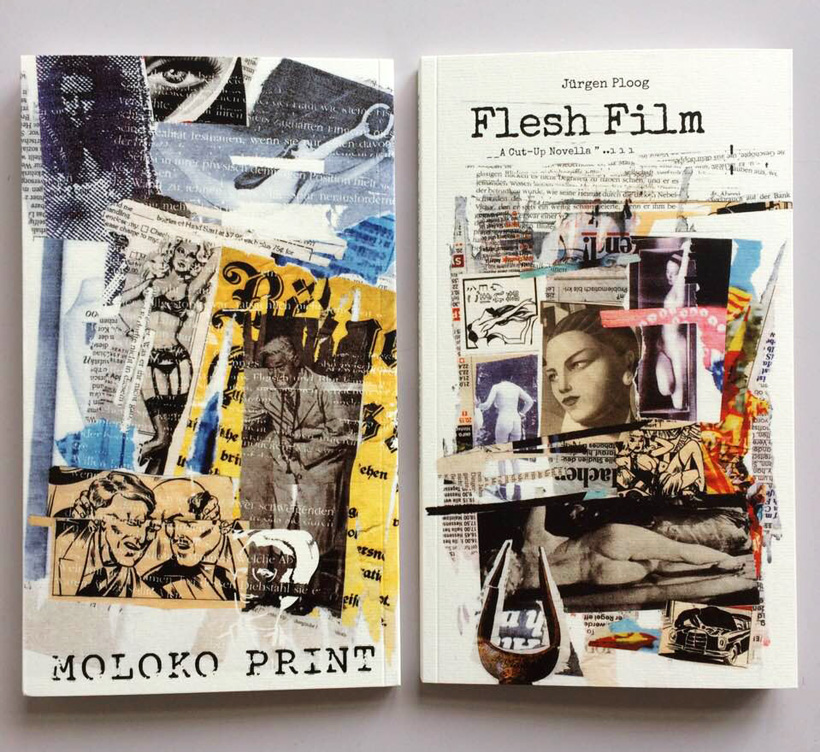

Author: Jürgen Ploog

Author: Jürgen PloogPublisher: Moloko Print, Schönebeck, Germany

Year: 2018

Size: 240 x 140 x 10 mm

Pages: 122, offset printed and perfect bound

Language: English

With collages by Jürgen Ploog

Artwork & Design: Robert Schalinski

Edward S. Robinson writes in his introduction to ‘Flesh Film’ for Reality Studio:

“Where the precise origins of the cut-up lie remain the subject of debate in certain circles, although no one would dispute the fact that it was Burroughs who formalized the method, provoking controversy in the literary establishment, and who is the writer with whom the technique will be forever associated. Burroughs himself acknowledged myriad literary precedents, and accredited Brion Gysin with the actual ‘discovery’ of the method, quite by chance, in 1959. Of those involved in the first collection of cut-ups, Minutes to Go (1960) — Burroughs, Gysin, Sinclair Beiles and Gregory Corso — only Burroughs would subsequently pursue cut-ups further. From Burroughs’ central point, however, radiated concentric rings of influence as other authors took his proclamation that ‘cut-ups are for everyone’ as a call to arms against language control and the narrow confines of linear narrative structures.

The European mainland spawned a remarkable second wave of post-Burroughsian cut-up authors to expand upon his principles and took the technique deep into new territories. Jürgen Ploog belongs to this lineage of vigorous, exciting, cut-up practitioners which includes Claude Pélieu, Mary Beach, and Carl Weissner.

There is an abundance of evidence to suggest that the cut-ups have begun to undergo something of a renaissance in recent years, and that we have the Internet to thank for this. This should not be considered too surprising, really. As Burroughs theorized, ‘life is a cut-up.’ He observed that that ‘every time you walk down the street, your stream of consciousness is cut by random factors… take a walk down a city street… you have seen half a person cut in two by a car, bits and pieces of street signs and advertisements, reflections from shop windows – a montage of fragments.’ As such, a leading function of the cut-up was to produce a mode of narrative that more accurately reflected the way we experience life in the modern world. If anything, the world in which we find ourselves is more fragmentary and jumbled than ever: the media overload that is contemporary culture, not to mention the Internet, is by nature fragmented, and as such forges a fragmented perception, and to this end, the cut-up is a more accurate reflection of our fragmented realities now than at the time when the cut-ups were in their heyday in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

What Ploog achieves in Flesh Film is a text that exists within its own space, drawing on Burroughsian tropes while demonstrating the experimental flare of his successors, while also looking forward with a distinctly twenty-first century aesthetic. Perhaps this is due in part to his re-creation of a Burroughsian world, often set in exotic and mystical places and populated by all sorts of shady characters — and Mugwumps. Equally, though, it is again due to taking a fundamentally random mode of writing and harnessing it. Ploog freely admits to editing his cut-ups, the cutting, splicing and reconfiguring of text analogous to the cutting and editing of film. A flesh film, no less.”