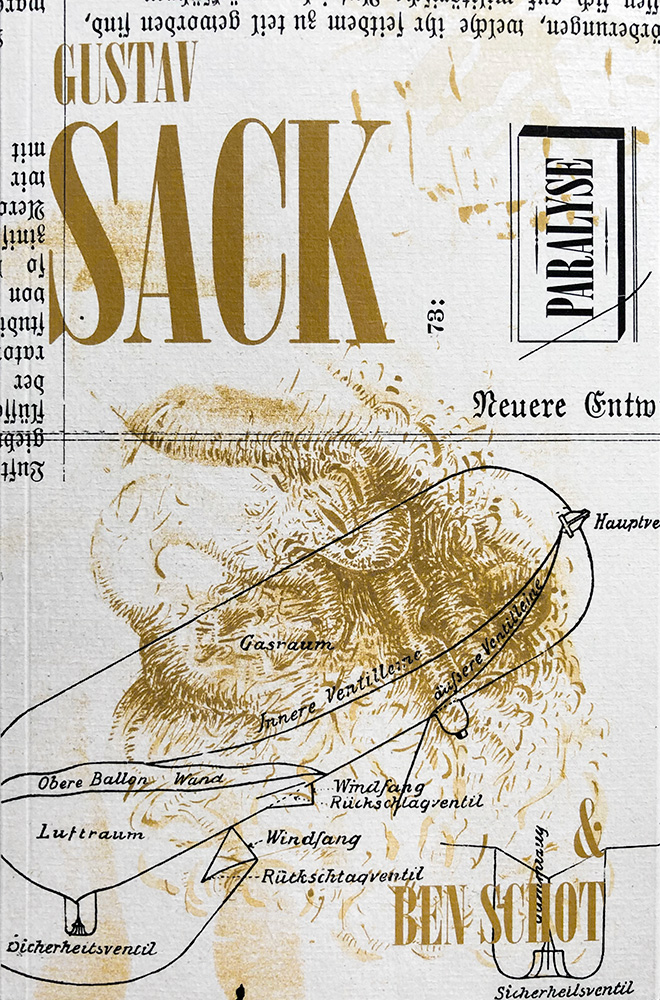

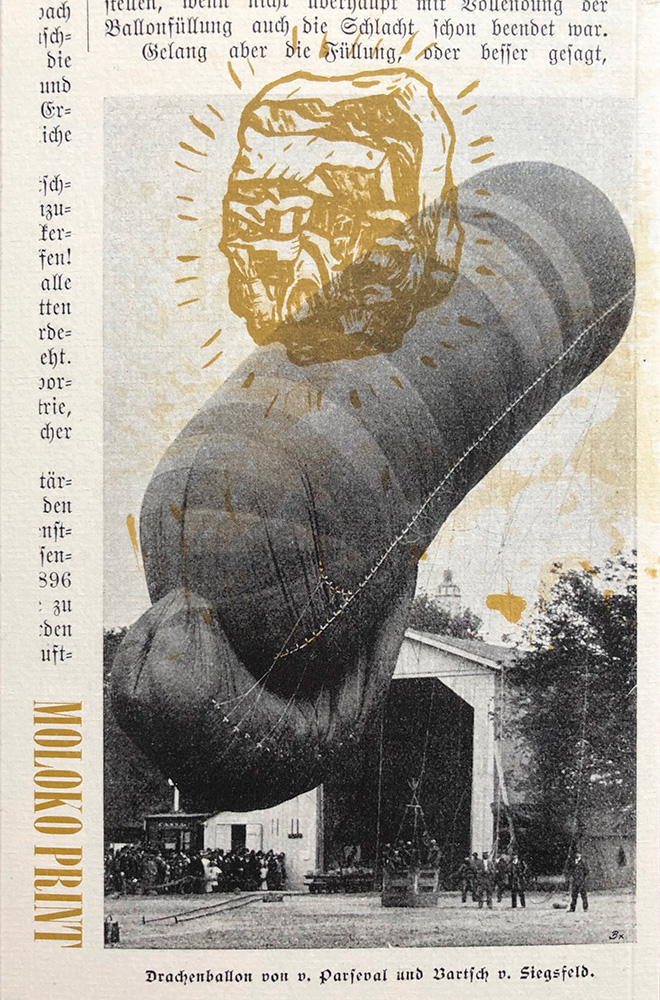

Paralyse is the title of a novel that Gustav Sack conceived and started in 1913 but never had the chance to finish. The novel was to revolve around the delirious ideas and fantasies of a poet/philosopher who, like Sack’s inspiration Friedrich Nietzsche, suffers from dementia paralytica in the final stages of syphilis. In a letter to his fiancee Paula Harbeck Sack explains that the main character of his novel will be “physically completely miserable, incapable to recollect or think logically, while lapsing into the wildest, most fantastic yet optimistic delusions; a glowing embrace of life and at the same time helpless as a child”. Moloko+ has now published the opening chapters of Sack’s hallucinatory novel, in which the main character’s syphilitic deliria gradually manifests itself and contrasting ideas fuse in a sublime nihilistic fire. Designed by Robert Schalinski and illustrated by Ben Schot this book is another fine publication in Moloko’s expressionist series.

Gustav Sack (1885-1916) grew up in the German village of Schermbeck, close to the Dutch border and the industrial Ruhr district. He attended the grammar school of the nearby town of Wesel and did German Studies and Natural Science at the universities of Greifswald, Münster and Halle before dropping out in 1910. Sack developed an interest in literature during his grammar school days, when he discovered Shakespeare, Shelley, Byron, Schopenhauer and many others and started writing himself. His wild and intoxicated student days were reflected in his first novel Ein verbummelter Student, written in 1910 when Sack was 25 years old. Despite Sack’s high expectations the novel was rejected by a Munich publisher that same year, but determined to pursue a career as a writer, Sack moved to the Bavarian capital anyway in 1913.

In Munich – in those days a mecca of German bohemianism – Sack and his future wife Paula Harbeck got in touch with the literary avant-garde and the first generation of expressionists. But the outbreak of World War I and his inevitable mobilisation made anti-militarist and anti-nationalist Sack decide to leave the country and take refuge in Switzerland. Being treated as a deserter by both the German and Swiss authorities, finding his financial support cut completely by his family and being separated from Paula, whom he had just married, left Sack financially and emotionally bankrupt. He returned to Germany in 1914, reported to the military authorities and was sent to the trenches of the Somme front a month later. In poems and an extensive correspondence with Paula he documented the insanity of the trench war for the next year and a half. After having been arrested for misconduct and insubordination, Sack was transferred to the psychiatric ward of a military hospital, where he stayed for a while and then was reunited with his wife. In 1916 they moved back to Munich. Just as Sack had reconnected with the avant-garde circles there and Paula had managed to raise interest in his work, Sack was sent to the front again – this time to Romania – where he was killed in action a couple of weeks later. None of Sack’s major works saw publication during his lifetime, but through the efforts of Paula they were published posthumously and then were acclaimed by leading authors such as Thomas Mann, Ernst Jünger and Theodor W. Adorno.

In Munich – in those days a mecca of German bohemianism – Sack and his future wife Paula Harbeck got in touch with the literary avant-garde and the first generation of expressionists. But the outbreak of World War I and his inevitable mobilisation made anti-militarist and anti-nationalist Sack decide to leave the country and take refuge in Switzerland. Being treated as a deserter by both the German and Swiss authorities, finding his financial support cut completely by his family and being separated from Paula, whom he had just married, left Sack financially and emotionally bankrupt. He returned to Germany in 1914, reported to the military authorities and was sent to the trenches of the Somme front a month later. In poems and an extensive correspondence with Paula he documented the insanity of the trench war for the next year and a half. After having been arrested for misconduct and insubordination, Sack was transferred to the psychiatric ward of a military hospital, where he stayed for a while and then was reunited with his wife. In 1916 they moved back to Munich. Just as Sack had reconnected with the avant-garde circles there and Paula had managed to raise interest in his work, Sack was sent to the front again – this time to Romania – where he was killed in action a couple of weeks later. None of Sack’s major works saw publication during his lifetime, but through the efforts of Paula they were published posthumously and then were acclaimed by leading authors such as Thomas Mann, Ernst Jünger and Theodor W. Adorno.