Georg Trakl (1887-1914) grew up as the sixth of seven children in a well-to-do protestant family in Salzburg, where his father made a living as a hardware dealer. His mother was addicted to opium and had a disturbed relationship with her children. The upbringing of Georg and his younger sister Grete, with whom he developed an intimate relationship, was left to a young Alsatian woman. The governess, Marie Boring, acquainted the Trakl children with French language and literature and introduced Georg to the poetry of Rimbaud, Verlaine and Baudelaire. They made a lasting impression on the nervous and sensitive boy. Georg first tried his hand at his own poetry as a 13-year-old student at grammar school, an education which he failed to finish and had to abandon in 1905. By then he was already experimenting with all sorts of drugs: opium, morphine, ether, barbiturates, alcohol and nicotine. Georg’s subsequent apprenticeship at a Salzburger pharmacy gave him access to an even wider range of drugs and soon he and Grete, who had developed into an exceptionally talented pianist, found themselves immersed in all sorts of intoxications, which coloured Georg’s growing literary output and pushed his relationship with Grete into the realm of incest.

After the death of father Tobias in 1910, the Trakl family landed into financial problems. Georg had to sign up as an army pharmacist in Vienna for a year, while Grete moved to Berlin, where she married the 34 years older publisher Arthur Langen. After having failed to set up his own business as a pharmacist, Georg focused on his poetry, which still showed influences of French symbolists but also paved the way for the later expressionists. Trakl saw his works published in Ludwig von Ficker’s renowned magazine Der Brenner from Innsbruck, and made the acquaintance of important people of the Austrian avant-garde circles, among whom Oskar Kokoschka. Ludwig Wittgenstein was so impressed by Trakl’s original, hallucinatory and groundbreaking work that he awarded him a grant that allowed the poet to concentrate on his work without financial worries. Soon after that, however, World War I broke out and Trakl, being a pharmacist, was sent to the eastern front as a medical army official. There he suffered from bouts of depression and after having witnessed the hanging of civilians and being in charge of many horribly wounded soldiers after a lost battle in Gródek, Ukraine, he suffered a nervous breakdown. Trakl killed himself with an overdose of cocaine. His sister Grete shot herself a couple of years later.

After the death of father Tobias in 1910, the Trakl family landed into financial problems. Georg had to sign up as an army pharmacist in Vienna for a year, while Grete moved to Berlin, where she married the 34 years older publisher Arthur Langen. After having failed to set up his own business as a pharmacist, Georg focused on his poetry, which still showed influences of French symbolists but also paved the way for the later expressionists. Trakl saw his works published in Ludwig von Ficker’s renowned magazine Der Brenner from Innsbruck, and made the acquaintance of important people of the Austrian avant-garde circles, among whom Oskar Kokoschka. Ludwig Wittgenstein was so impressed by Trakl’s original, hallucinatory and groundbreaking work that he awarded him a grant that allowed the poet to concentrate on his work without financial worries. Soon after that, however, World War I broke out and Trakl, being a pharmacist, was sent to the eastern front as a medical army official. There he suffered from bouts of depression and after having witnessed the hanging of civilians and being in charge of many horribly wounded soldiers after a lost battle in Gródek, Ukraine, he suffered a nervous breakdown. Trakl killed himself with an overdose of cocaine. His sister Grete shot herself a couple of years later.

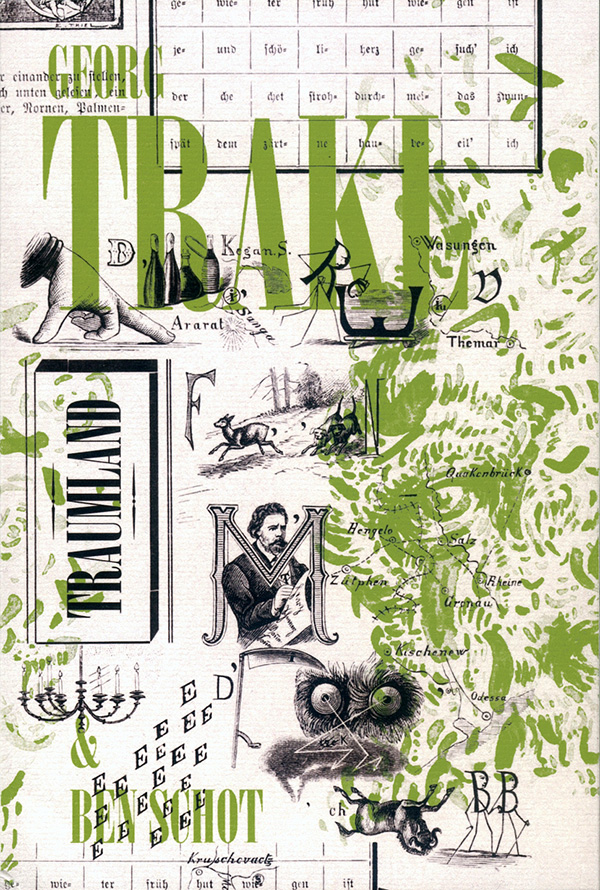

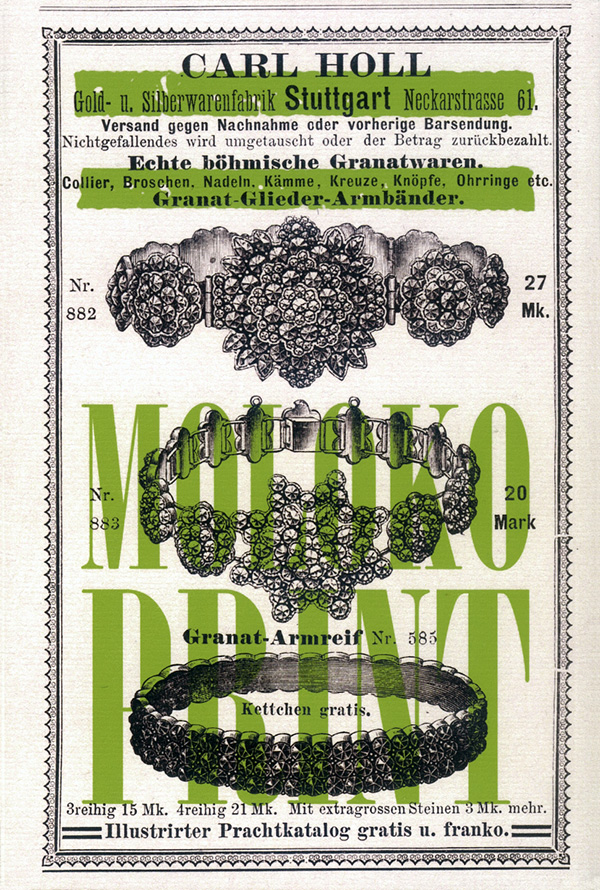

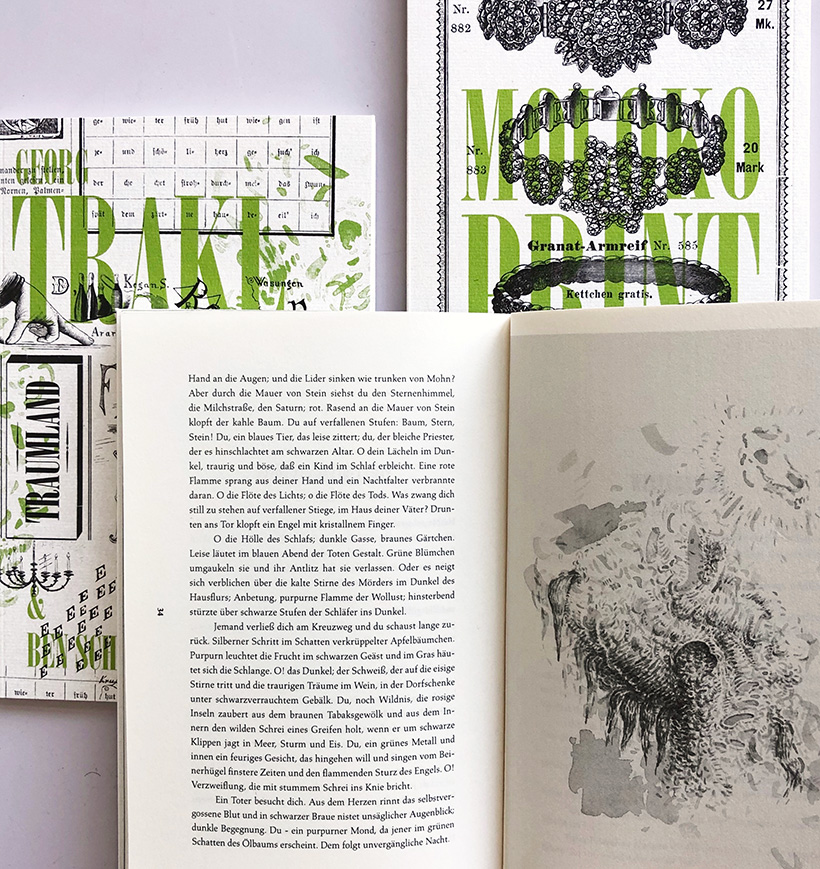

The Moloko compilation Traumland, beautifully designed by Robert Schalinski, brings together nine of Trakl’s hallucinatory prose fragments and prose poems plus a small number of aphorisms. Eight of the prose pieces have been illustrated in watercolour by Dutch artist Ben Schot. Among the selected prose is Trakl’s juvenile work Traumland. Eine Episode, which was published in the Salzburger Volkszeitung in 1906 when Trakl was 19 years old. Other prose poems have been culled from the posthumous compilations Sebastian im Traum (1915) and Offenbarung und Untergang (1947) and various other sources. Together the pieces form a surprising selection of tales and imagery that transcend poetry and prose and take the reader to the sublime highs and lows of Trakl’s intoxicated mind.